In a world where nearly every economic force seems engineered to move production overseas, is it still possible to make something in America — and do it competitively?

Over the course of four years, a small team led by Destin Sandlin set out to answer that question by doing something deceptively simple: making a grill scrubber. Not just designing one — actually building it from the ground up, with real materials, real tools, and real people. The goal wasn’t to talk about American manufacturing. It was to do it. And in the process, they unearthed something bigger: a hard look at what it takes to make physical things in a post-industrial economy.

Manufacturing in the Shadow of Globalization

The modern manufacturing landscape wasn’t always like this. A generation ago, middle-class Americans could count on factories as stable sources of income and pride. Sandlin, whose parents were both union auto workers in Alabama, remembers the smell of cutting fluid as the smell of productivity. But those jobs — like so many others — began to vanish with the advent of NAFTA, CAFTA, and the gravitational pull of globalization.

Outsourcing wasn’t a villain in a black hat. It was economics. Cheaper labor, fewer regulations, global shipping lanes protected by decades of U.S. military dominance — these things tilted the balance toward moving production abroad. And companies followed. They had to.

But what happens when the pendulum swings too far? What happens when a global pandemic hits and even basic medical supplies like face shields and N95 masks become impossible to source domestically?

You realize something: the knowledge chain has been quietly eroding.

Starting with Nothing

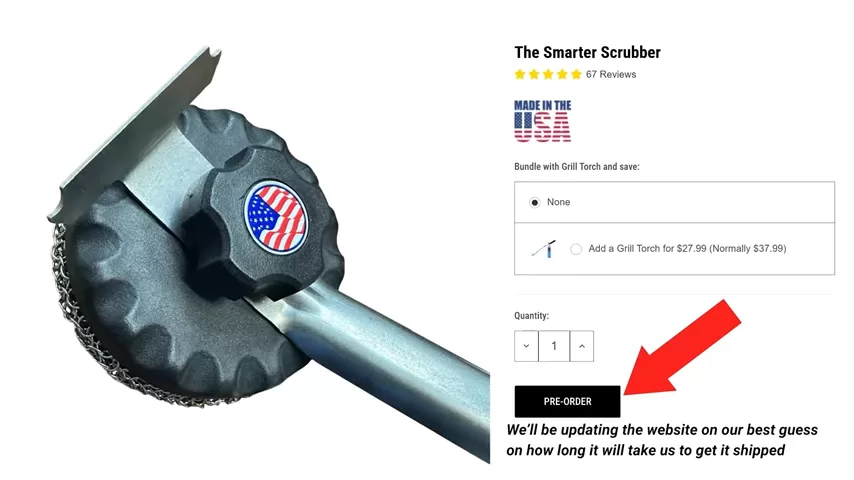

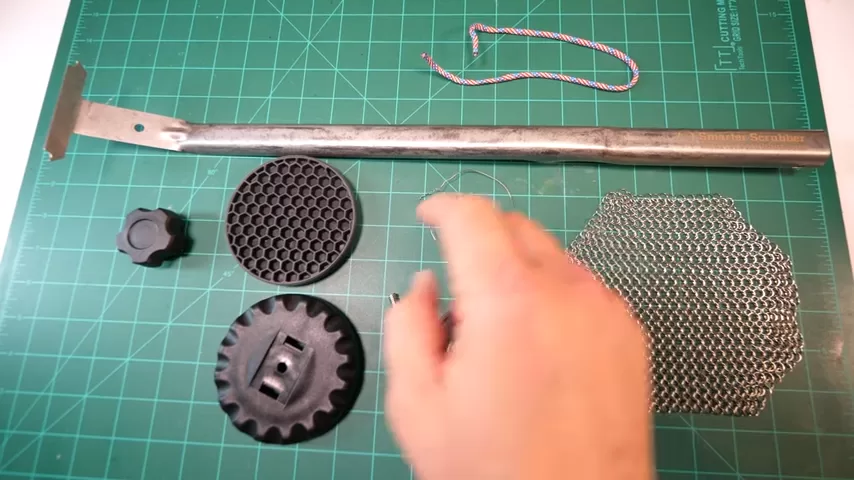

Sandlin’s goal was clear: make a product in America. The product? A bristle-free grill scrubber made of chain mail and metal — something safer than the wire brushes that have landed far too many people in the ER with bits of bristle embedded in their throats.

But deciding to make something in America and actually doing it are two very different things.

He quickly learned that even something as banal as a one-inch stainless steel bolt becomes a problem when you insist on “Made in the USA.” Prices quadruple. Suppliers disappear. Verifying origin is murky. Even when you think you’ve sourced American-made components, you find out — often too late — that they were quietly rerouted from China through another country.

Then there’s tooling — the craft of making molds for injection-molded parts. Few U.S. shops even offer it anymore. Some said outright, “We send the files to China.” That moment, Sandlin says, was when the experiment snapped into focus. America hadn’t just lost factories. It had lost the people who knew how to make the machines that made the parts.

The Real Cost of Outsourcing

One partner in the project, John Youngblood, had been burned by overseas manufacturing before. He had a hit product — a grill torch — but when he outsourced the tooling to Asia, those very same tools were used to make cheap knock-offs, which flooded Amazon at half the price. And the worst part? Amazon did nothing.

With this new product, Youngblood and Sandlin wanted to do things differently. No Amazon. No overseas tooling. Just high-quality parts, sourced and built with integrity.

They succeeded — mostly.

The Limits of Integrity

Despite every best intention, the team ran into limits. American chain mail? Too expensive. Domestic quantities too low. A secondary supplier in India promised to meet the shortfall — only for the team to discover, embarrassingly late, that the chain mail was likely just Chinese metal routed through India.

Integrity costs money. And sometimes, even money isn’t enough.

That’s not to say the effort failed. On the contrary, what emerged was a product designed with precision, tested under pressure, and built — as much as possible — by American hands. The Smarter Scrubber is more than a grill tool. It’s a case study in modern manufacturing.

Why It Matters

This isn’t about patriotism or politics. It’s about resilience. In a brittle supply chain, local capability becomes national security. When pandemic waves disrupt shipping, or when geopolitical tensions rise, your community needs to be able to make things — not just code, not just content — but actual, physical things.

The golden rule isn’t just a moral suggestion; in manufacturing, it becomes survival. Do unto others — make things that last. Support jobs you’d want for your own kids.

The Bigger Picture

Sandlin’s YouTube channel, “Smarter Every Day,” helped fund and tell the story of this experiment. But the real story isn’t on camera. It’s in the hands of people like Logan — a young tool and die apprentice whose skillset could quietly shape the future. It’s in the memory of Roger — a craftsman whose decades of wisdom now live only in the tools he left behind.

Tool and die work won’t trend on social media. But it’s the bedrock of every manufactured thing you’ve ever held. Lose it, and you lose the ability to build. Period.

A Call to Build

This isn’t a pitch for a product (though Sandlin makes one, and it’s compelling). It’s a pitch for people — for caring about how things are made, for valuing the hands and minds that make them, and for investing in the slow, deliberate work of rebuilding.

If you’re a business owner, maybe you take a little less profit and invest in local supply. If you’re a young person, maybe you consider tool and die over finance. And if you’re just a person who buys things, maybe — just maybe — you buy fewer cheap things and one or two excellent ones.

Because one day, your community might need someone who knows how to make a mold. And when that day comes, it won’t matter how many apps you have. It’ll matter how many people still remember how to make things.

That’s not nostalgia. That’s strategy.

And it starts one product at a time.