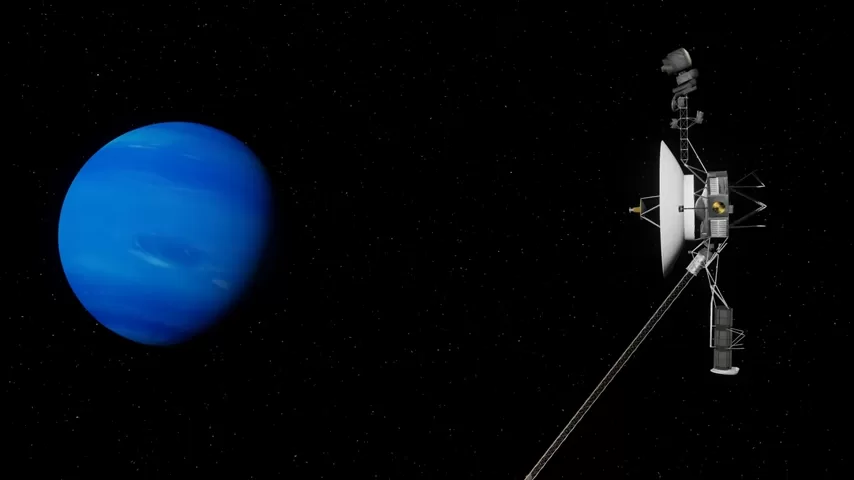

On February 14, 1990, Voyager 1 captured one of the most famous and humbling images in human history: a tiny speck floating in a vast sunbeam, a “pale blue dot” suspended in the cosmic dark. That dot was Earth. Just 34 minutes later, the spacecraft’s cameras were turned off—permanently.

Since then, Voyager 1 has become the most distant human-made object in existence, drifting ever farther from our Sun. Today, it’s over 24 billion kilometers (15 billion miles) away. But why were its cameras shut off? And if we turned them back on, what would they see?

Let’s explore the astonishing journey of Voyager 1’s cameras—what they were capable of, why they were deactivated, and what cosmic sights they might capture if they could somehow be brought back online.

A Camera Beyond Its Time

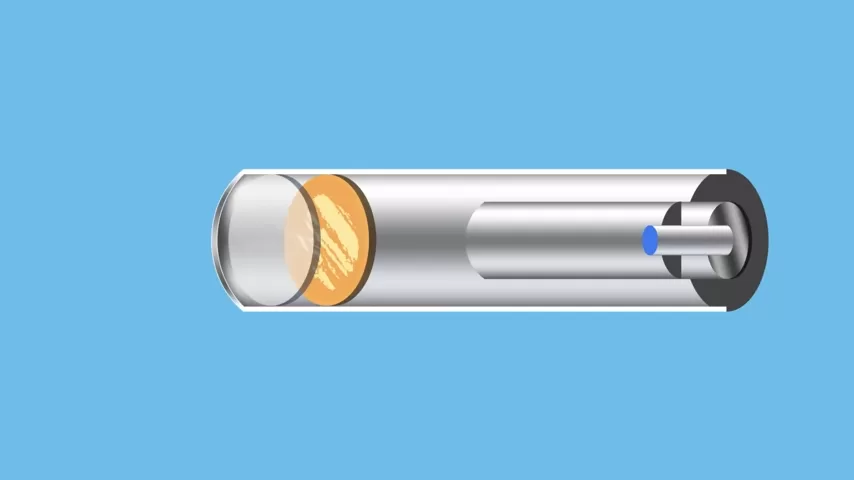

Voyager 1 was launched in 1977 with one mission: to explore the outer planets. It came equipped with two vidicon cameras—early analog-to-digital TV-style instruments, each with a resolution of 800 x 800 pixels, capturing grayscale 8-bit images.

- The wide-angle lens captured large, full-planet views.

- The narrow-angle lens zoomed in on detailed features like rings and moons.

To create color images, Voyager used a rotating filter wheel—violet, blue, green, and orange. The spacecraft would take several images of the same object using different filters. These would then be combined and digitally colorized back on Earth to recreate what the human eye might see.

In essence, Voyager saw the universe much like we do, using basic light filtration and signal processing. But what happened once those signals were captured?

How Voyager Transmitted Its Images to Earth

Once a grayscale image passed through Voyager’s optics and hit the photoconductive plate in the vidicon tube, it created a series of electrical currents—essentially an image signal. This data was stored on magnetic tape, then transmitted to Earth whenever Voyager had a clear signal path.

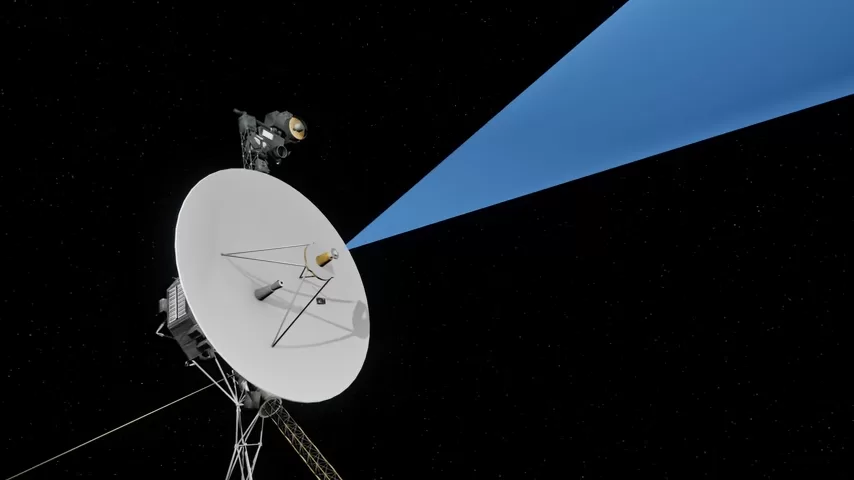

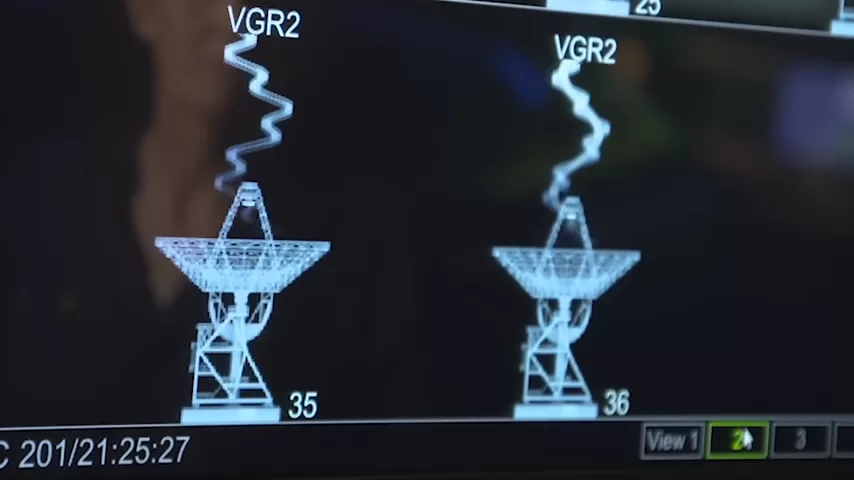

At launch, Voyager had a healthy data rate of 115,000 bits per second, enough to send an entire image in under a minute. Today, due to distance and signal degradation, that rate is just 160 bits per second—meaning it would take over 8 hours to transmit a single photo. On top of that, each signal takes 21 hours just to reach Earth.

In short: it’s slow, complicated, and increasingly fragile.

So Why Were the Cameras Turned Off?

When Voyager took the Pale Blue Dot image, it was already 6 billion kilometers from Earth—too far for detailed photography. All visible planets had been documented, and the spacecraft was heading toward interstellar space, where visual imaging was no longer scientifically useful.

Here’s why the cameras were turned off:

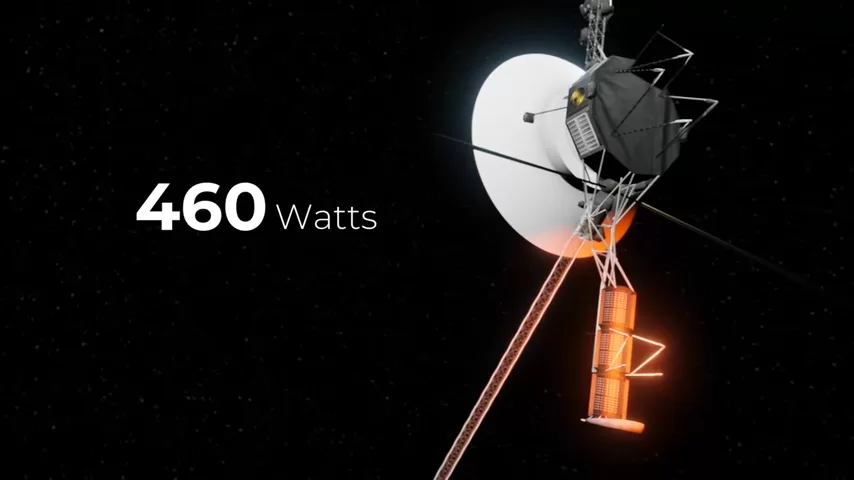

- Power Conservation: Voyager 1 is powered by an RTG (Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator). Each year, the RTG produces about 4 watts less than the year before. Today, it produces only 57% of its original output. The cameras, and especially their heaters, draw over 40 watts.

- Instrument Prioritization: To detect when Voyager would leave the heliosphere and enter interstellar space, engineers needed to focus on plasma, cosmic ray, and magnetic field instruments.

- Obsolete Software and Hardware: The camera-control software was deleted from onboard memory, and the analysis tools used back on Earth no longer exist. Reviving the system would require rebuilding 1970s-era code and support infrastructure.

- Harsh Conditions: The cameras have been exposed to deep space for decades, without heaters or maintenance. Even if powered on, they likely wouldn’t function due to thermal damage and decay.

Could We Turn the Cameras Back On?

Technically, no.

Even if power was rerouted and memory restored, the lack of modern software support and risk to other onboard systems make it too dangerous. NASA’s priority now is preserving Voyager’s scientific data stream for as long as possible—not risking it all for a low-resolution photo.

What Would Voyager See If It Could Take a Photo Today?

Contrary to what you might expect, Voyager is not floating in total darkness. Even from 23–24 billion kilometers away, sunlight is still 16 times brighter than moonlight here on Earth. That’s bright enough to read a book by—but not bright enough to reveal much through a tiny 800×800 sensor.

So what would a photo look like?

- The Sun would appear as a faint star.

- The planets—if visible at all—would be tiny, dim dots.

- The stars and constellations would look identical to how we see them on Earth, because Voyager is still within our stellar neighborhood.

To see a change in the constellations due to parallax, Voyager would need to travel thousands of light-years. That will take millions of years, long after contact is lost and Earth may be a memory.

Why the Pale Blue Dot Still Matters

That final photograph wasn’t taken for science. It was taken for perspective.

At the request of Carl Sagan, the Voyager team turned the camera around and captured our planet from the edge of the solar system—just a single pixel suspended in a sunbeam.

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us.”

– Carl Sagan

That one image continues to remind us how small, fragile, and unique our world is—especially in a universe that grows emptier the farther we explore.

Conclusion: Eyes Closed, But Not Blind

Voyager 1 may never see again, but it continues to listen. Its instruments still send back invaluable data from a region of space no human craft has ever explored before.

In a way, turning off the cameras helped Voyager stay alive. It gave us a longer window to learn about our solar system’s edge—and a chance to receive data from interstellar space itself.

And though its camera may never turn back on, its final image is eternal: a pale blue dot in the cosmic dark, reminding us of the only home we’ve ever known.

If you enjoyed this breakdown and want more content like it, consider supporting the creator on Patreon, where you can help choose future topics and join the conversation.

And don’t forget—there’s a Space Shuttle LEGO giveaway in the next video! To enter, leave a comment about your favorite space moment of all time, and follow the link in the description.